It’s Time To Rethink How We Test

Unit testing, component testing, integration testing, acceptance testing, exploratory testing… You’ve heard the terms, maybe even practiced testing at various levels on the Test Pyramid. But, a lot has changed in just a short period of time. Isn’t it time how we test changed, too?

Image by frender on iStock by Getty Images

The Traditional Testing Model

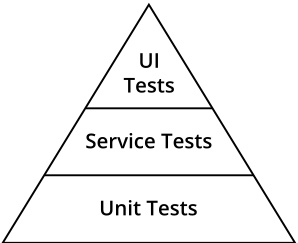

The traditional testing model supports tests at various levels, which can be practically described by the Test Pyramid. The Test Pyramid, as presented by Mike Cohn, holds that Unit Tests make up the largest suite of tests in an application, followed by service tests, which test the functionality of the system just beneath the UI (e.g. Web Services) and finally UI tests, which test the system through interactions with the User Interface.

Test Pyramid

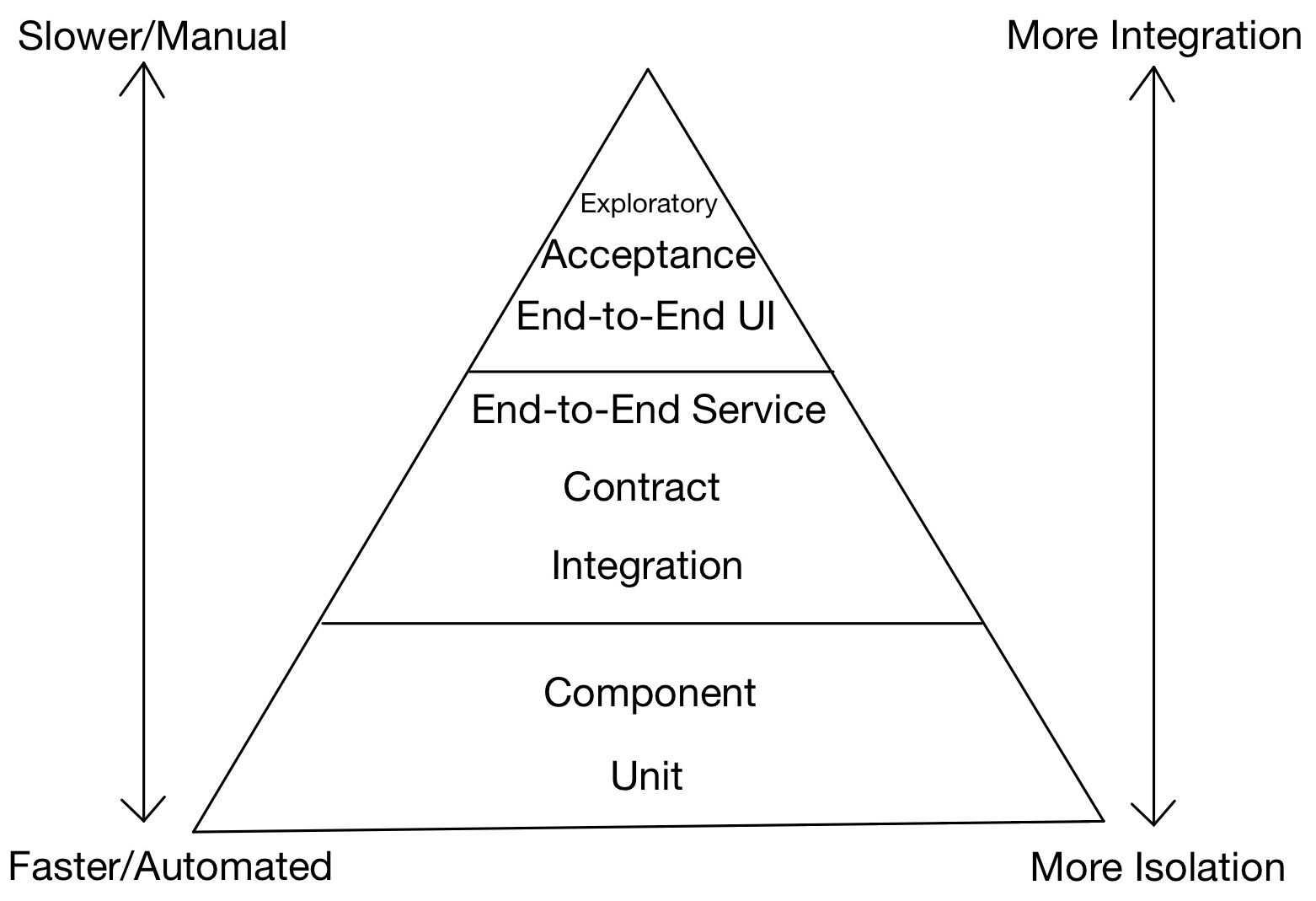

The different layers of the Test Pyramid can also be further broken down.

Updated Test Pyramid

Unit Tests

Unit tests, at the base of the pyramid, represent the largest suite of tests for any software system. They test granular functionality in relative isolation. Unit tests are meant to be run fast and frequently.

We don’t get too hung up on social vs isolated unit tests; it’s more important to have valuable tests than it is to be overly dogmatic. As was discussed in Code Quality, Not Test Coverage, our definition of unit tests (and we think it’s a good one :) are tests that can be collectively run fast (under 5min, in most cases) and in relative isolation. By isolation, we mean without external systems, which are outside the system under test.

Component Tests

In practice, component tests might be blended together with unit tests. And indeed, our definition of unit tests could work well with a blend of unit tests and component tests. So, then what is a component? A component is an encapsulated piece of system functionality.

A component can be a small library, module or a package. Or it could just be a group of logical entities within the same system that together provide some piece of functionality. If you have a group of software entities and together they provide some modicum of functionality that is not fully represented by any one individual piece, then you could likely consider them, together, a component.

Integration Tests

Integration tests are one step up from unit tests. Like unit tests, integration tests test relatively granular functionality. However, unlike unit tests, integration tests depend on the availability of external systems. Integration tests may make assumptions about external systems being available for basic functionality, or they may test the interactions with external systems in a very detailed way. In many cases, an integration test may look and feel a lot like a unit test that can’t be tested without the availability of one or more external systems.

Contract Tests

Contract tests test the interfaces between applications. When two systems communicate with each other, there is either an explicit, or an implicit contract. The contract is the data exchange agreement (format and protocol) between those systems which allows them to interact successfully. If either of those systems breaks the contract then they will be unable to successfully communicate with each other. Contract tests validate that the contracts between systems are valid and that they are adhered to by the systems communicating under those contracts.

End-to-End Service Tests

End-to-end service tests are broad stack tests, which can require multiple services, layers, components and external systems to evaluate. The functionality they test touches many pieces of the system. For that reason, they are time-consuming tests to execute. However, using service endpoints, instead of a UI as the primary interface makes these tests easier to execute programmatically and less susceptible to volatile UIs.

End-to-End UI Tests

End-to-end UI tests evaluate broad system functionality using the UI as the entrypoint. They may comprise a more complete suite of tests than acceptance tests, but they approach testing from the same perspective, that of the user.

Acceptance Tests

Acceptance tests, or functional tests evaluate whether the high-level system features work correctly. Acceptance tests test the system from a user’s perspective. They answer the question, “Does the system do what it’s supposed to do?”

Exploratory Tests

Exploratory tests are manual tests that are evaluated by testers who creatively evaluate the workings of the system from a user’s perspective that may not be evaluated by even the best automated tests. The purpose of exploratory tests are to find the corner cases and the usability problems that may have slipped through the cracks.

What About Infrastructure Testing?

Infrastructure as Code (IaC) and an increased reliance on Cloud platforms inject another consideration for testing: infrastructure testing. It’s not that infrastructure testing was never done before. However, with IaC, the door for infrastructure testing has opened considerably since infrastructure can now more closely resemble traditional software.

Infrastructure is not software

Infrastructure is not software… well, not exactly, anyway. Infrastructure has different constraints placed upon it, which poses the question, “How does infrastructure testing fit into the test pyramid?” Consider unit tests, which by our definition means that they are (1) fast and (2) run in relative isolation. How can you execute infrastructure in isolation? Isn’t the point of provisioning/updating/destroying infrastructure to affect external systems?

Jim Brikman of Gruntwork discusses IaC testing in the context of Terraform in his post 5 Lessons Learned From Writing Over 300,000 Lines of Infrastructure Code. In his article, he makes an argument for rethinking the test pyramid for infrastructure to look more like the following.

- End-To-End Tests = Entire Stack

- Integration Tests = Multiple Modules

- Unit Tests = Individual Modules

We think he was on the right track. But, we also think that’s an oversimplification. Like with traditional software development, infrastructure unit tests should be fast. However, infrastructure events are rarely “fast.” Traditional unit testing might allow hundreds of tests to run in minutes or less. That is never going to happen with any kind of infrastructure testing. So, we offer the following definition for infrastructure unit tests.

Infrastructure Unit Tests are select high value infrastructure module tests that validate infrastructure events and configuration that are expected to occur.

You might be thinking, “That doesn’t sound like high coverage testing.” In the traditional sense of unit test coverage, it’s not. However, time is not a commodity with infrastructure tests; it’s a luxury. Additionally, how infrastructure is used can be more intentional than say, classes in traditional software development. So, intended scope of use can (and should) be factored in to get the highest value tests possible while still covering the maximum amount of infrastructure events and configuration.

Beyond Unit Testing

Infrastructure tests beyond individual modules don’t need to be as dogmatic as Integration Tests = X. The focus should be “Does the infrastructure I am provisioning/updating/configuring behave as it is expected to behave?” Infrastructure stack tests can be based on successfully answering that question. The tests that you choose to supply as a satisfactory response to that question should be the highest value tests for the intended scope of the infrastructure.

How To Test Infrastructure

Some specific details on how we test our infrastructure can be found in our posts Testing Terraform With Spock and Testing Terraform For More Than Just Compliance. We are strong believers that infrastructure tests that don’t actually provision infrastructure are not high value tests. The reason for this is that you cannot really validate the final state of infrastructure without provisioning it. Sure, there are tools out there that can make a somewhat educated guess, like Terraform plans. But they aren’t always accurate, and sometimes they are really far off. No, if you want to really know what your infrastructure is going to look like then you need to actually execute its event (provision, update, etc.) before you validate it.

Swiss Cheese Testing For Infrastructure

Infrastructure testing doesn’t end after provisioning. At least it doesn’t have to. The shortcomings of infrastructure testing are that they take a long time, and you can’t practically test every possible scenario. But infrastructure testing can be verified at multiple levels, including after the infrastructure is up and running with continuous validation and alerting mechanisms that can be used to reduce risks that may have been missed during Unit Tests and Stack Tests.

Putting It All Together

So, we still have a testing pyramid for software products. But the idea of completely isolated and strictly non-social tests, even at the unit test level, becomes less and less relevant as testing tools evolve and as we strive to include higher value tests. The introduction of Infrastructure as Code (IaC) further highlights the need for infrastructure tests as a significant component of any comprehensive testing strategy. And not unlike software testing, infrastructure testing also has multiple layers: Unit Testing, Stack Testing and System Testing.